Vaux Primary School

Contributor: Katherine Finley, Temple University Social Studies Pre-Service Teacher

“We [the students at the Institute

of the Colored Youth] are nevertheless preparing ourselves usefully for a

future day, when citizenship in our country will be based on manhood and not on

color.” – Jacob White, Jr. 1855

I do not wish to seem

proud of separate schools for our children, but I say, if the children that we

have to educate, must study by themselves, let some competent teacher who fully

sympathizes with them have them a charge.

—

The

Christian Recorder, 1876

Jacob White, Jr., a powerful young orator and lifelong friend of Octavius V. Catto and graduate of the

Institute for Colored Youth, became a distinguished educator, using his position as principal of Vaux Primary School to prepare generations of young African Americans for citizenship. Like his friend Catto, he believed that education was the pathway to increased participation and opportunity for blacks. Under his leadership, Vaux became one of the most important public schools headed by an African American.

The Roberts Vaux Grammar School, also known as the Roberts Vaux Consolidated School and the Vaux Primary School over the years, was established in 1836 in honor of Roberts Vaux (1786-1836), the first president of the Philadelphia Board of Education. A Quaker, Vaux was an abolitionist and ardent supporter of free public education . for all children. In 1827, he founded the Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Public Schools, which worked to ensure that schools were tuition free and open to all school-age children. His goal was realized through the common school laws of 1834 and 1835 and the Consolidation Act of 1836. However, the schools that were established then were largely segregated. Black and white student would often share the same building, but would be segregated into different rooms. Occasionally, the students were integrated as long as black class enrollment did not exceed that of whites. Black educators were also not allowed to teach white students, so black students had white teachers, many of whom shared the racial perceptions of the time. In 1854, discrimination became more overt over time, when Pennsylvania legalized the separation of the races in all public schools if twenty or more African American pupils could be educated together. By the timethis law was repealed in 1881, segregation had become entrenched in Philadelphia. Vaux Primary School initially met in the basement of Mother Zoar African Methodist Episcopal Church on Brown Street. above 4th Street.

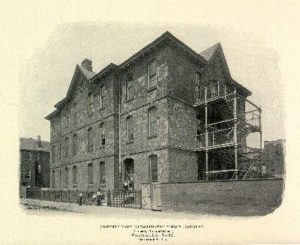

When White arrived as principal of Vaux, he was also the only teacher at Vaux. In his first year, he increased the enrollment to 200, which led to the removal of the school out of the basement of Zoar. White’s dedication as principal allowed the school to expand quickly to over two hundred students, and it relocated to a building on Randolph Street near Parish Street. Vaux came to be known as the flagship black public school in Philadelphia and White one of the most respected African American education and civic leaders in the city. On February 10, 1876, the growing school enrollment led to relocating again to a school building on Wood Street above 11th Street, previously the William D. Kelley School, named to honor another Catto associate in the battle for emancipation, African American military service, and civil rights. (The William D. Kelley School is now located at 1601 North 28th Street.) The expansion of Vaux allowed for the addition of grades, making the school the only black grammar school also offering a secondary education to African American students.

In his position as principal, White worked with Catto, both using their positions as prominent educators and leaders in Philadelphia to further the civil rights cause. The same year that White became principal of Vaux, he and Catto organized the

Pennsylvania Equal Rights League. The League lobbied for civil and political rights for African Americans in Pennsylvania. The two men heavily focused on the issues of streetcar and voting rights and served as liaisons to Congressman William Kelley and Senator Thaddeus Stevens in the fight to amend the U.S. Constitution to expand citizenship rights and strike down racial barriers. The League also strove for educational reform. Both Catto and White advocated for separate schools for African American students with African American teachers, like the Roberts Vaux Grammar School and the Institute for Colored Youth. Their intention was not to exacerbate segregation between races, but to ensure that African American students were receiving a quality education from teachers who fully understood their situation. Following Catto’s death in 1871, Jacob White continued his work in education and civil rights activism. Other leading educators, activists, writers and officials looked to him for authority and guidance until his death in 1902. Today, Robert Vaux School has been converted into the Promise Academy at Robert Vaux High School, located at 2344 W. Master Street The school was closed in 2013 as part of Philadelphia’s shutdown of 23 district-run schools. The displaced students were enrolled in Strawberry Mansion High School and Benjamin Franklin High School. It is now operated by Big Picture Philadelphia, a charter operation.