Did You Know

Thomas Nast, November 20, 1869, Harper’s Weekly. Source: Library of Congress

“There must come a change…which shall force upon this nation…that course which Providence seems wisely to be directing for the mutual benefit of all peoples.” – O.V. Catto Memorial

Forging citizenship and opportunity has been a process many have been striving for since the beginning of the country. It is a continuing issue in America today.

The United States Constitution, drafted in 1787, did not explain or define citizenship. However, it did mention “citizens of the States” and “citizen of the United States.” The Constitution gave Congress the power to set a uniform rule of naturalization, which conferred citizenship and gave state courts the authority to administer naturalization. Changes around citizenship were accomplished through legislative actions at the state and local levels, through judicial proceedings, and as a result of activism by individuals and groups.

The Naturalization Act of 1790 set the initial rules on naturalization: “free, White persons” of “good character“, who had been resident for 2 years or more. The law excluded Native Americans, indentured servants, enslaved persons, free blacks and Asians. However, since citizenship was granted at the state level and at the national level, some states granted it to some free blacks.

The 1790 Act was superseded five years later by the Naturalization Act of 1795, which changed the residency requirement to five or more years and that citizenship could only be granted to free white persons of “good moral character.” The Naturalization Act of 1798 amended this law and extended the residency requirement from five years to fourteen years and targeted the Irish and French for exclusion. In 1802, this law was replaced. The “free white requirement remained and the residency requirement was reduced to five years. An alien had to declare, at least three years in advance, intent to become a citizen. The 1802 act was the last major piece of naturalization legislation until the Civil War/Reconstruction era. Some minor revisions were introduced without changing the basic nature of the admission procedure. The most significant of these revisions occurred in 1855, when citizenship was automatically granted to alien wives of U.S. citizens.

In 1857 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the Dred Scott decision that “a negro, whose ancestors were imported into [the U.S.], and sold as slaves”, whether enslaved or free, could not be an American citizen.” This ruling complicated citizenship status for many blacks living in northern cities. As dissenting Justice John McLean noted: “At the time of the ratification of the Constitution, black men could vote in five of the thirteen states. This made them citizens not only of their states but of the United States.” Black leaders in northern communities, among them Frederick Douglass, Henry Garnet, William Catto (father of Octavius Catto), and attendees at a national conference of Presbyterian and Congregational ministers in Philadelphia, voiced their outrage to the ruling calling the decision “a sin against God, and a crime against humanity” meant to “degrade and rob free people of color of civil and political rights.” The activism of free blacks regarding citizenship is demonstrated through the Negro Convention Movement (1831-1864) in which a national network of blacks worked collaboratively to change laws in America. Their efforts advanced that “the elevation of the free man is inseparable from and lies at the very threshold of the great work of the slave’s restoration to freedom.” After Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, a new call to action for northern citizenship rights and opportunity was pushed forward by the National Equal Rights League and its state affiliates, whose members included a new generation of rising young black leaders, among them Octavius V. Catto.

“Citizens of the United States” was not defined by the Constitution until the ratification of the 14th Amendment in 1868. The Amendment reads: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” The 14th Amendment codified “birthright citizenship” and was one of three Reconstruction amendments that were transformational for America. The amendments established a new constitutional baseline in post-Civil War America that scholars often refer to as “America’s Second Founding”. Congressman John Bingham (Ohio), the primary author of the 14th Amendment’s citizenship clause (Section 1) sought to enshrine the Declaration of Independence’s promise of liberty and equality into the Constitution. This established a federal baseline for national citizenship. In some circles, this was seen as a positive broadening of what it meant to be American. In other circles, it was viewed with distain.

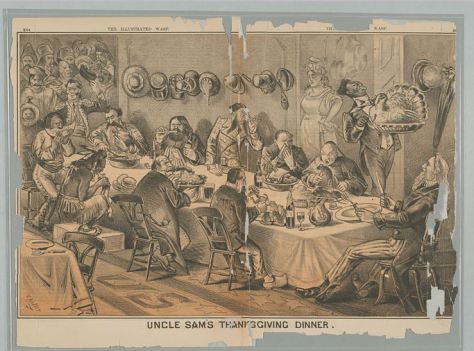

G.F. Keller, San Francisco Wasp, 1877. Source: Library of Congress

Congressional laws would, however, determine how and which “aliens” could become naturalized citizens or deemed citizens.

The Congressional enabling legislation for the naturalization aspects of the 14th Amendment was the Naturalization Act of 1870. This act allowed naturalization of “aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent”. It was silent about other races.

The Civil War and Reconstruction period brought on changes in America, as well as sparked the imagination around the world about what America meant. In 1865, the idea to create what was to become the Statue of Liberty was conceived by French abolitionist and ardent Union supporter Edouard Rene de Laboulaye and sculptor Frederic Bartholdi. The statue was dedicated in 1886 in New York City harbor on Ellis Island and became a “beacon” to the world of the promise of America.

However, official policies were not as liberal as the ideals expressed on the statue. The 1882 Immigration Act imposed a 50-cent tax on every immigrant and banned the entry of “any convict, lunatic, idiot, or any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.” Between 1903 -1917 new restrictions on immigration were imposed. People with physical or mental defects, beggars, imbeciles, illiterate adults, unaccompanied minors and most Asians were excluded. In 1921, the Quota Act capped annual entries at 350,000 immigrants based on a national origins quota. The quota provided immigration visas to two percent of the total number of people of each nationality in the United States as of the 1890 national census. The method was skewed in favor of immigration from western European nations, while severely curbing immigration from areas perceived to be undesirable. Nonetheless, between 1892 and 1954, more than 12 million immigrants entered the U.S. through Ellis Island and became potential new citizens.

Citizenship by birth in the United States, however, was not initially granted to Asians until 1898, although Asian-origin populations have historically been in the territory that would become the United States since the 16th century. It was also not until June 2, 1924 that Congress granted United States citizenship to Native Americans born in the United States. But even after the Indian Citizenship Act passed, some Native Americans weren’t allowed to vote because the right to vote was governed by state laws. American Samoans are still not given citizenship at birth today. They are considered American nationals and must apply to be naturalized to become citizens.

In 1965 inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Hart-Celler Act at the Statue of Liberty. This law finally abolished earlier quota systems based on national origin (race) and established a new immigration policy based on reuniting immigrant families and attracting skilled labor to the United States. The policy laid out in this law continues to be the bases of our system today, however with quotas still determining immigration levels. Naturalization is open to these immigrants and their children born in America are citizens by birth.